by Mike Foxworth, 8/13/2022. 13-minute read

In Brief

- Pain is a tool our brain uses to keep us safe.

- With PN, pain can become chronic and useless since the sensations are not signs of imminent danger and provide no information useful for treatment.

- A brain that understands just how safe it is, can adjust to the sensations (just like it can adjust to the taste of spicy food) without creating pain.

- When PN pain is mild, temporary use of simple tools or moderate medications may give enough relief to allow the patient to learn and adapt.

- When the PN patient is in great distress, look for all reasons, not just physiological indicators.

- Looking for all reasons is expensive and not commonly supported by big insurance companies.

- When the PN patient is in great distress, do not accept “no” from the insurance companies. Fight back and win.

Pain is a Tool of the Brain

Pain is a tool of the brain designed by nature to protect us by interpreting signs (both external and internal) for possible danger and, if danger is detected, prompting us to do something to avoid that danger.

This way of thinking about pain is distinctly different than the limited “natural” understanding of pain that we grow up with. The “natural” view of pain is “if my body is damaged, I feel pain”. But that view of pain is too simple. It is not consistent with many experiences. If we are busy, we may not feel pain when a minor injury occurs: have you ever looked down in some surprise at a bloody spot on your leg where you scraped it while running? Damage to the body was not sufficient to create pain when it happened. Your damaged skin sent signals, but your brain did not think there was enough danger to try to get you to immediately stop running. On the other hand, physical damage is not necessary to have pain. We can feel pain in the absence of actual physical damage: such as “butterflies in the stomach” when about to give a speech or a headache after an emotional conflict with someone. Your brain can sense danger in the context of a social situation and create pain to persuade you to be cautious about that situation.

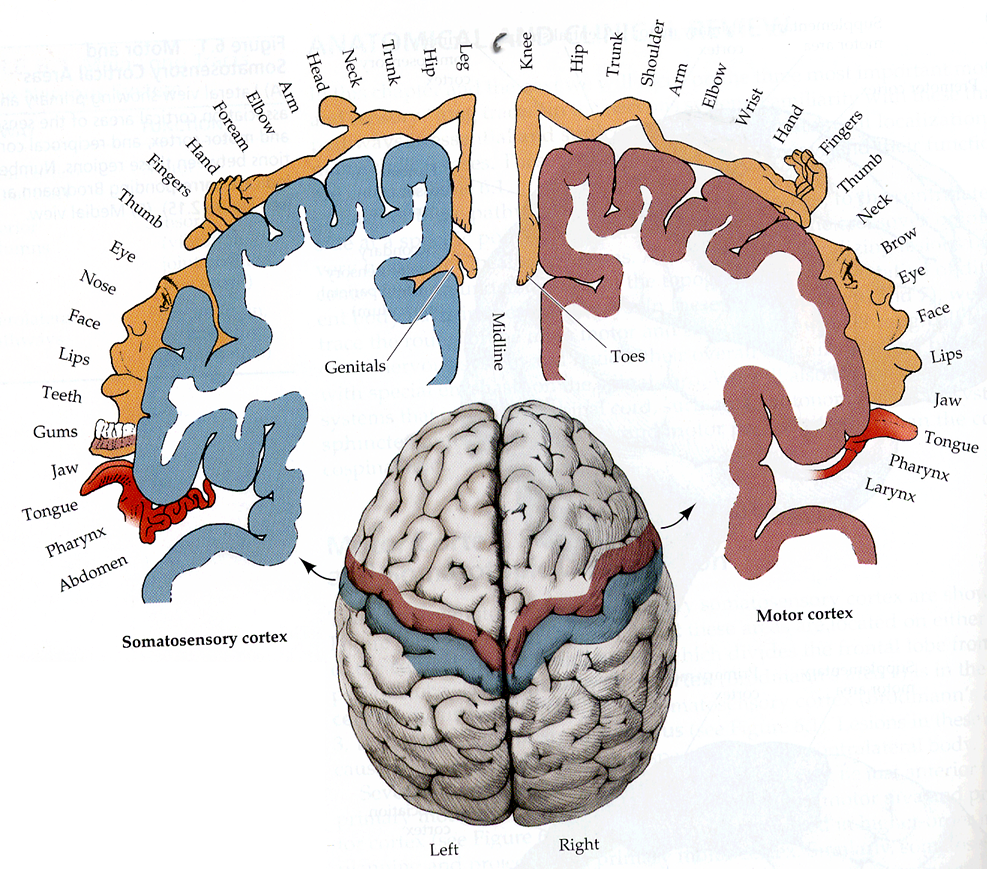

The too-simple “natural” understanding of pain reflects our built-in “mental map” of the body. There are indirect connections between sensors in our body to specific parts of our brain (the somatosensory cortex). This “map” allows us to say “my toe hurts” when we stub our toe. We are born with this map, though experience can change the map (like all other parts of the brain).

Growing up, everyone experiences damage to the body, the brain creates pain to get us to “fix things” and the brain uses this “map” to help us identify those parts of the body that seem to be damaged. Early life “trains” us to think of pain this way.

And it is not just us. Doctors get extensive training on using reports of pain to try to identify parts of the body that are experiencing damage. They do not want to miss identifying that damage.

Unfortunately, when we get PN, that early training may not serve us, or doctors, well.

PN usually causes sensory changes. The brain is likely to notice such changes and create thoughts of discomfort or pain. For symmetric distal polyneuropathy (the common form of PN that shows up first with damage to the neurons that are in the feet) the person will use that “mental map” to roughly identify the toes or feet as where the sensory signals seem to be coming from. (Note: rarer forms of PN may not allow the patient to clearly identify a specific location.)

Initially, that PN pain can be helpful. It may prompt us to go to the doctor, be diagnosed, possibly find (and maybe correct) the cause, and be properly advised about what to do.

Further Pain Is of Limited Benefit

After diagnosis, any further pain is of limited benefit. It does not guide us to any further actions to stop the PN from progressing. All further pain is now chronic. Chronic pain, by definition (from the Institute for Chronic Pain), does not protect us. PN is a slow process. We are never in any immediate danger from PN. When we take the recommended actions (principally exercising, diet, sleep, financial and housing planning) there are no further immediate actions available to deal with the long-term danger PN poses.

Science has no practical way to measure signals coming from our peripheral nervous system. That is true of all disease, not just PN. But most disease attacks the body, not just the nervous system. If the nervous system (including our brain) is largely intact (that is, it has not already been damaged by PN and not badly damaged by long experience with some other form of chronic pain), there is a reasonable chance that our brain can successfully generate useful pain. That is, pain that we and doctors can use to find and fix the damage. But PN damages the signaling system itself by killing neurons and their supporting cells. It is not certain what, if any, signals are being sent by diseased neurons (there is active research on that). Yes, erroneous signals may still be coming from the body’s PN-damaged nerves and, if so, they can be alarming or annoying. But such signals are not useful. Any pain our brain creates from them is not useful either. Again, doctors usually have no additional treatments to stop the PN from progressing.

We will be better off by getting the brain to relax, stop interpreting the situation as dangerous and, thus, stop creating all that pain. Modern approaches to chronic pain emphasize getting (“teaching”) the brain to stop trying to “protect us” from things we cannot do anything about.

We will be better off by getting the brain to relax, stop interpreting the situation as dangerous and, thus, stop creating all that pain

How Can Relief be Found?

Traditional approaches for treating chronic pain in other parts of the body are based on a concept that pain is a “marker of tissue damage.” So, for things like back or knee pain, a lot of “treatment” is based on theories that there is some damage to the body that can be “repaired.” For instance, epidural injections into “disk bulges.” As the previously cited Institute for Chronic Pain article states, such treatments may provide some temporary relief but do nothing to address the chronic pain itself. Such treatments cannot improve the physical state of the body part (such as the back). In many cases, there is no objective evidence that the “damage” can even generate nociceptor signals. In many cases, “sham” or “placebo” treatments work just as well.

Modern approaches for treating chronic pain in other parts of the body emphasize that pain is created by the brain in response to the entire body and mind context. That context includes signals from the body (if any) but not just those signals. That context includes past and current experiences and the patient’s understanding of the situation. Since the brain is the ultimate controller of chronic pain, treatment emphasis is placed on education, psychology and prompt relief. Prompt relief is important because long-lasting, severe chronic pain is a serious health risk. See this article for a description of the many types of associated adverse health effects.

Chronic pain due to PN is a special case of chronic pain, in that there is no large body of conventional medical specialists out pushing procedures to stop PN damage. That is because almost no progress has been made in treatments to correct the physical damage (Note: “Almost” but not none; testing is currently being conducted on some forms of treatment for special cases. The future is not all dark.) That has not prevented many “snake oil” vendors from pushing “treatments” with unverified claims that they can stop PN damage.

Aware that there are no available creditable treatments to stop PN’s progressive damage, traditional medical approaches to chronic pain from PN (neuropathic pain) put their emphasis on the sensations (the signals) and changing the way those signals are handled in the brain. This approach can be called “try-this-and-if-that-doesn’t-work-try-something-a-bit-stronger”. Where “stronger” implicitly acknowledges the existence of adverse side effects or additional expense.

Thought of that way, with a disease where the tissue damage cannot be changed, then, clearly, the patient may think of PN pain as something that cannot be eliminated. It can only be “managed” and “adapted to.” With that mindset, thinking that PN chronic pain is entirely due to physical damage and knowing that physical damage cannot be fixed, leads, quite logically, to a patient with severe pain believing that PN chronic pain is inevitable. With that, depression and desperation can become the rule. But that mindset is wrong.

Modern treatment stresses that pain is “a marker of the perceived need to protect body tissue” and if that perception can be changed then pain and suffering can be eliminated. These approaches focus on education to change “one’s conceptualization of pain” [from the longer Moseley article referenced below]. To some extent it builds on techniques of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to emphasize one-on-one intensive work between patient and counselor to change destructive thinking patterns. Not to “accept” pain but to “eliminate” suffering. More narrowly, eliminate the suffering of those with severe pain issues. As opposed to elimination or distortion of the sensory signals (over which we have little control and cannot measure). These modern techniques explicitly recognize how “natural” it is to think “pain = tissue damage.” They recognize how hard it can be for a patient to broaden their view of pain beyond this natural notion. But relief from suffering requires this broadened view.

There are huge individual differences in patient reports of pain. A survey of our membership in 2018 showed that about a third of our members had big problems with pain. The traditional approach ignores the source of these individual differences. It is implicitly assumed that there are unknown physiological reasons (either in the person or the type of PN) why one person has little pain, while another is consumed by pain. Yet there is plenty of psychological and physiological research on how life history and experience can affect the amount of pain a person feels in response to a stimulus.

The work of Clark and others [see https://pnsnetwork.org/meeting-notes-february-5-2022/ for videos and references to books] shows that stress and trauma can generate pain when no or insufficient physiological damage can be found.

The work of Moseley and others shows how perception of pain reflects perceptions of danger, that the entire context of the person’s current physical and emotional situation affects that perception. Further, as described in the Institute for Chronic Pain document cited above, that prior experience with long-term pain can generate neurological (that is, physical) changes that can amplify signaling and change the brain structures used to process those signals. [Moseley is available in many popular YouTube videos. My favorite. His classic book “Explain Pain, 2nd edition” is very good though expensive in print and a bit hard to read in Kindle form. A more recent article talks about the Explain Pain approach https://www.jpain.org/article/S1526-5900(15)00682-3/fulltext#relatedArticles and how it has been tested in clinical practice and how it can be misinterpreted by those unconsciously wedded to default “pain = tissue damage” thinking.]

The traditional approach to PN pain management does not reflect the work of researchers represented by Clarke and Moseley. The traditional approach spends little time examining the entire patient history. In fact, modern medical practice is dominated by insurance standards that allow little time for doctors to “spend time” talking to the patient.

Basic Approach – Patient centered education.

Principle #1 – Keeping the patient in charge. All pain is real, personal and unique. It reflects that person’s history and all the other elements of that person’s current life. The patient must stay alert to the situation and not relinquish total control to doctors or supporters who cannot “know everything”.

Principle #2 – Educate the whole patient. Being controlled by the brain, pain can only be resolved or eliminated when the person feels safe from immediate danger. The person with PN pain is in some sense alarmed. The pain will not back off until the person’s brain-based pain control systems understand there is no reason to be so alarmed. But this is not a mere academic exercise. With enough bad experience, psychological and physiological changes become set up and do not magically disappear. It can take significant time and a mix of professional skills to bring the patient along.

Principle #3 – Pain can interfere with learning, so it is important to bring the patient back to comfort as quickly as possible, perhaps using drugs as helpful tools when appropriate.

For many, simple counseling may be more than adequate to find something that provides sufficient relief. Learning the concepts of “what is pain” and “what is really going on” may be enough to educate the patient to have a correct understanding of the actual physiological dangers and what can and should be done about those dangers.

Other patients may find the sensations a bit hard to deal with, perhaps interfering with sleep or peaceful activities. For this, adoption of relatively simple and low-side-effect approaches may make sense.

TENS units can distract a patient away from unwanted sensations. A TENS unit does not remove those sensations. Instead, it provides harmless overriding sensations (“electrical tingling”) to occupy the portions of the brain concerned with danger (the TENS user uses a control to set sufficient signal strength). After a session (typically 30 minutes), the prior PN sensations (if they exist) may not immediately resume triggering pain. The brain quite sensibly notes that nothing horrible happened while being distracted by the TENS, so why immediately start sending more danger signals about those sensations? While the effect of any single TENS session may be temporary, there can be a lasting benefit if consistent use over a period serves to convince the brain to stop focusing on future harmless PN sensations. To quote Lorimer Moseley: “…any credible evidence of danger to body tissue can increase pain and any credible evidence of safety to body tissue can decrease pain.” A successful TENS session is credible evidence of safety.

Additionally, the brain sends pain to get the patient to do something. Using a TENS is doing something. Hence, some control of the situation has been restored to the patient. There have been several large studies on TENS use with PN. They do not show 100% success, but all the studies recommend that they be tried. The basic principle is “just get used to” the PN sensations, so they are not thought of as harmful. Or at least not harmful enough to disrupt life. Like getting used to spicy food, “eating your broccoli” or wearing a tie to work.

NOTE: Capsaicin patches, like Salon Pas and Icy Hot, work by using the same principle of distraction away from the chronic pain focus.

Relatively mild drugs (such as gabapentin) may help some patients by modifying the way the brain functions. All such drugs carry risk. Gabapentin can cause dizziness and other side effects and can be dangerous for patients with lung problems such as COPD. But that risk may be judged to be worth taking if the patient can move away from other problems such as lack of sleep or work issues. In principle, since we do not actually know how these drugs create such benefits (other than the placebo effect), it makes sense to consider ways to stop taking them as the patient learns more about the nature of chronic pain. There are many medications and “treatments” in this general category. They all have some risk, some expense, limited research, limited success rates (not much different than placebo), but, like any successful placebo, are judged to be helpful by some patients. If the patient settles on a particular approach and “gets on with life” and stops constantly searching for pain relief, that is a sign that the brain is no longer in constant alarm mode. It becomes a personal choice to continue a treatment, hopefully with little collateral damage.

Nevertheless, continued reliance on such treatments reflects at least some misunderstanding of what pain is. If the patient is otherwise doing OK, devoting much time and expense to develop a deeper understanding may not be worthwhile.

When Chronic Pain Poses a Serious Problem

When chronic pain poses a serious problem, successful pain relief must look at personal history. Successful pain relief explicitly acknowledges the role of pain and how chronic pain can misuse that role to cause far more damage than the original physiological issue.

The too-simple “natural” understanding of pain reflects our built-in “mental map” of the body.

Many patients are not in a stable state. Their brains have not accepted that PN is not an immediate danger. The longer a chronic pain situation is in place (perhaps building on conditions from childhood or PTSD or family or work stress) the greater the potential for physical changes to the brain and sensory system that make it harder to cope. As the earlier article on effects of severe chronic pain describe, there is evidence of feedback mechanisms with chronic pain that cause physical changes in the brain and spinal cord. Neuron connections and neurotransmitter receptors can be added that make the patient more reactive to sensations. In such cases, immediate relief may be needed to give the patient time to calm down about PN and reflect on the situation. A slow, gradual “try-this-try-that” process using moderate drugs may not be appropriate if the patient’s life is sufficiently disrupted (though some drugs must be brought on slowly to allow the patient to adapt to an effective dose). Chronic pain can put a lock on a person’s life that can prevent needed learning and adjusting. The alligators may need to be subdued to drain the swamp. For this to happen, it may be appropriate for medical providers to quickly move to strong drugs that provide relief sufficient to allow learning to happen. The drugs can be backed off later as the patient deals with the wider issues that are making pain so dominant in life.

Fly in the Ointment

There are many names for this approach. There is not yet a firm set of names that have been widely accepted. Most of them are variations on combinations of physical therapy (that gradually exposes a person to painful stimuli to learn what can be safe) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. This article calls it Graded Exposure Therapy. Moseley calls his approach “Graded Motor Imagery” as it makes extensive use of graphics and visual illusions to get the patient to accept that usual ways of thinking about things can be wrong. But, as successful as these techniques have proven to be for some, this is not one-size-fits-all. It is inherently dependent on interactions between patient and professional. Of course, that is true of all psychological and counseling practices, not just treatment of chronic pain.

There is a big fly in this ointment. Insurance companies are not on board with this. There are likely complex personality, personal experience and history reasons why a person is having huge problems with PN pain. Tracking them down is not something a 15-minute session with a primary care doctor or neurologist is likely to find. Answers will not be found in a pill bottle. Drugs are normally the least expensive component of treatment. The insurance company is quite happy to participate in the “try this, try that” dance while refusing to provide access to appropriate medical professionals. It is up to the patient to demand care and seek professional medical responses. Insurance companies are legally bound to provide access to psychologists, counselors and psychiatrists. Yet many restrict coverage to in-network specialists and then simply state (as if they had no choice in the matter) that no in-network providers are available or impose visit restrictions and wait times incompatible with proper care. Or they provide standard rates of payment that are so low no providers will accept that rate as full payment. Medicare is especially bad in this regard as it refuses to pay if the specified rate is not accepted as full payment.

But the patient is not defenseless. All insurance contracts have protest or grievance processes. Use them. I have. And I have won. Several times. Medical necessity letters can be written. Slow, cumbersome processes, seemingly designed to discourage their use, are the norm. But severe chronic pain is a life-threatening condition. It can be treated. Demand treatment.

Mike – thanks for writing and sharing this on the PNSN Blog. I suffer more from numbness than I do pain, but as I end my 5th year of PN, I’m starting to experience more pain. So, I’m making a note of this essay, and will certainly be reading it again. This will be a helpful resource to have. I could directly relate to a lot of what you covered. I’ve taken many of the drugs you mentioned, and also have a home version of a TENS unit that I use before going to bed at night — it does help me get to sleep. I also get low level laser light treatment therapy on a regular basis. I’ve discovered that at least some of my pain is caused by inflammation. I know this because I apply frozen hydrocollator packs to the areas experiencing pain, and within a few minutes, the pain subsides. Note: these hydrocollator packs are the same ones used in training rooms to provide moist heat to athlete’s achy joints, but they work great in reverse, i.e. as a cold pack. Interestingly, I’ve never seen them marketed to be used in this way. Thx again for writing this!

Rich, thanks for the comment. I was not aware of hydrocollator packs. I should take a look.

While I usually say, “I have little pain,” the truth is that there were many years of sleepless or sleep-limited nights. My perspective on that was that I was functionally OK. I never found myself desperate for some cure.

It was not until I did the research on my wife’s struggles with chronic pain that I found the materials and perspective I cite in the essay. I still have that same “pain” but knowing what it is (and is not) helps me considerably. Obviously, my hope is that sharing this will help others. But working with my wife shows the limits of “knowledge” alone (as Moseley and some other studies confirms). But working with my wife, with help from counselors, also showed that it could gradually help. And be hugely irritating when her husband bungles into “lecturing” mode.